IBM denied this, saying the only human intervention occurred between games.

Īfter his loss, Kasparov said that he sometimes saw unusual creativity in the machine's moves, suggesting that during the second game, human chess players had intervened on behalf of the machine. Kasparov did not take this possibility into account, and misattributed the seemingly pointless move to "superior intelligence." Subsequently, Kasparov experienced a decline in performance in the following game, though he denies this was due to anxiety in the wake of Deep Blue's inscrutable move.

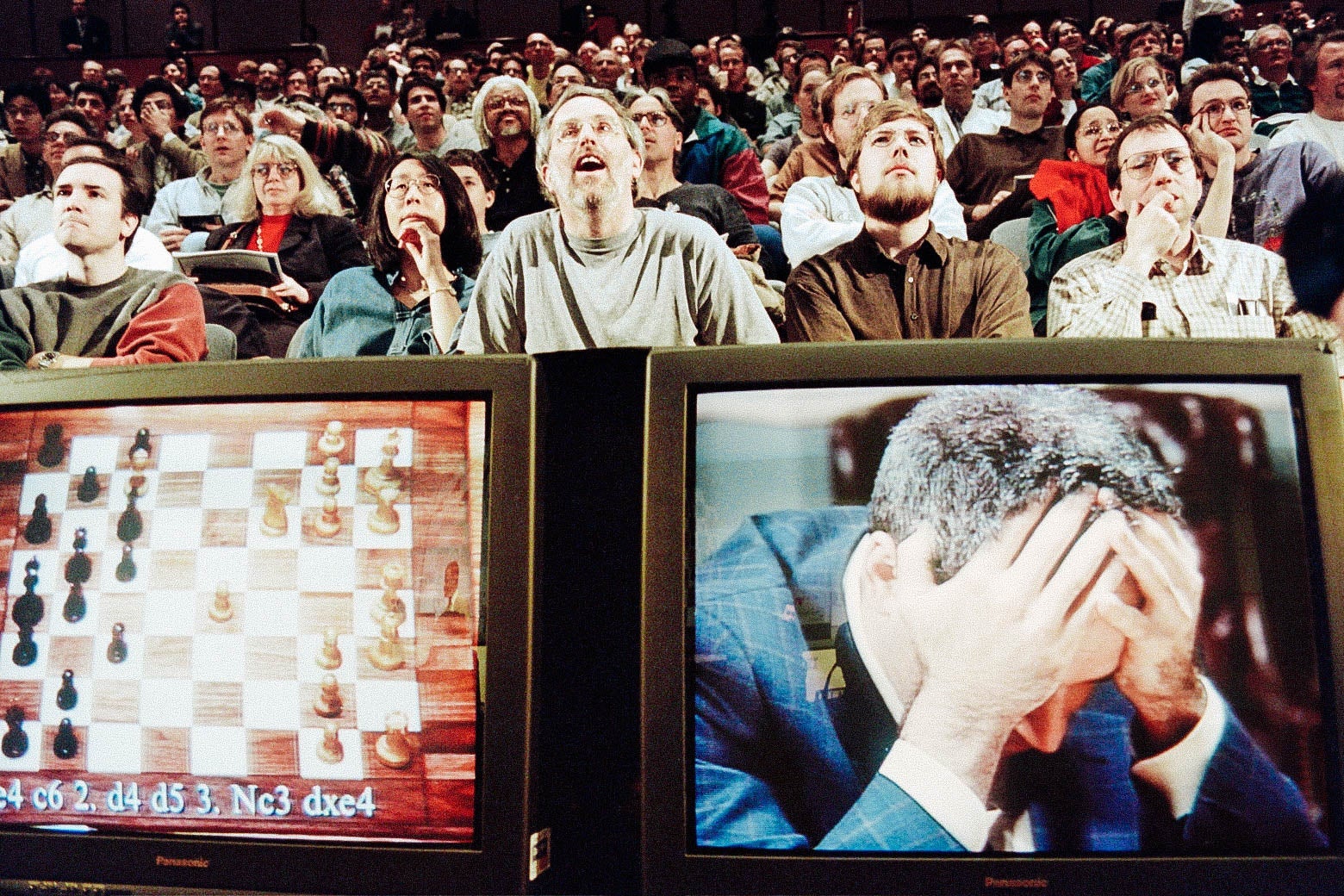

1996 deep blue chess code#

In the 44th move of the first game of their second match, unknown to Kasparov, a bug in Deep Blue's code led it to enter an unintentional loop, which it exited by taking a randomly-selected valid move. David Levy and Monty Newborn estimate that each additional ply (half-move) of forward insight increases the playing strength between 50 and 70 Elo points. The version of Deep Blue that defeated Kasparov in 1997 typically searched to a depth of six to eight moves, and twenty or more moves in some situations. Deep Blue won the deciding game after Kasparov failed to secure his position in the opening, thereby becoming the first computer system to defeat a reigning world champion in a match under standard chess tournament time controls. ĭeep Blue's hardware was subsequently upgraded, doubling its speed before it faced Kasparov again in May 1997, when it won the six-game rematch 3½–2½. However, Kasparov won three and drew two of the following five games, beating Deep Blue by 4–2 at the close of the match. In the first game of the first match, which took place from 10 to 17 February 1996, Deep Blue became the first machine to win a chess game against a reigning world champion under regular time controls. Subsequent to its predecessor Deep Thought's 1989 loss to Garry Kasparov, Deep Blue played Kasparov twice more. Garry Kasparov playing a simultaneous exhibition in 1985 Several books were written about Deep Blue, among them Behind Deep Blue: Building the Computer that Defeated the World Chess Champion by Deep Blue developer Feng-hsiung Hsu. Today, one of the two racks that made up Deep Blue is held by the National Museum of American History, having previously been displayed in an exhibit about the Information Age, while the other rack was acquired by the Computer History Museum in 1997, and is displayed in the Revolution exhibit's "Artificial Intelligence and Robotics" gallery. In 1997, the Chicago Tribune mistakenly reported that Deep Blue had been sold to United Airlines, a confusion based upon its physical resemblance to IBM's mainstream RS6000/SP2 systems. In 1995, a Deep Blue prototype played in the eighth World Computer Chess Championship, playing Wchess to a draw before ultimately losing to Fritz in round five, despite playing as White. Īfter Deep Thought's two-game 1989 loss to Kasparov, IBM held a contest to rename the chess machine: the winning name was "Deep Blue," submitted by Peter Fitzhugh Brown, was a play on IBM's nickname, "Big Blue." After a scaled-down version of Deep Blue played Grandmaster Joel Benjamin, Hsu and Campbell decided that Benjamin was the expert they were looking for to help develop Deep Blue's opening book, so hired him to assist with the preparations for Deep Blue's matches against Garry Kasparov. Jerry Brody, a long-time employee of IBM Research, subsequently joined the team in 1990. Their colleague Thomas Anantharaman briefly joined them at IBM before leaving for the finance industry and being replaced by programmer Arthur Joseph Hoane. After receiving his doctorate in 1989, Hsu and Murray Campbell joined IBM Research to continue their project to build a machine that could defeat a world chess champion. The machine won the World Computer Chess Championship in 1987 and Hsu and his team followed up with a successor, Deep Thought, in 1988.

While a doctoral student at Carnegie Mellon University, Feng-hsiung Hsu began development of a chess-playing supercomputer under the name ChipTest.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)